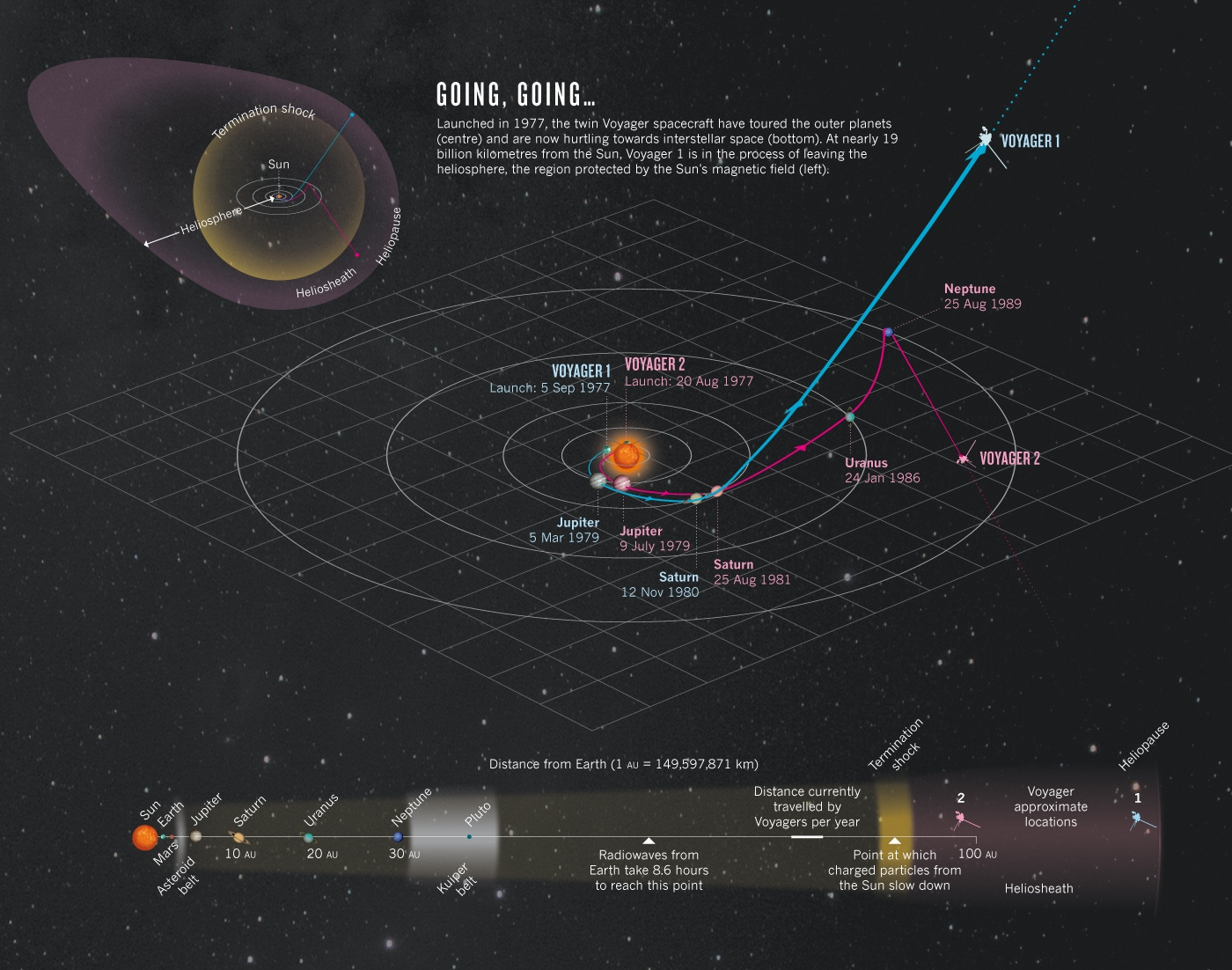

It’s hard to think about a billion. If you had a billion seconds to do something, that would be over 30 years. So now think about 15 billion… that’s how may miles Voyager 1, launched in 1977, is from the earth. Voyager 1 is the furthest humanity has ever knowingly sent something and despite being originally intended for a mission of just a few years, it is still going strong 47 years later. Until a few months ago when it stopped going strong and started sending back random streams of meaningless data.

It takes almost an entire day to send information to Voyager, so when the information coming in stops making sense, most people would probably be within their rights to think, well that was a good run, and call it a day. Not Todd J. Barber or any of the other members of the Voyager mission team who managed to identify a failed chip and reformat a 47 year old spaceship from 15 billion miles away. If you want to hear the whole story, you can listen to Todd tell it on the Hard Fork podcast - just skip to 50:25.

This is an amazing story just on the facts but I want to focus on something else. I want to focus on Todd and his fellow rocket scientists at NASA. If you didn’t listen to the story I recommend that you do so before continuing…

Last week was the final day of a class that I teach at Parsons, called Finding the Adjacent Possible. The name for this course comes from an idea I picked up from Stuart Kauffman, an evolutionary biologist. He was referring to the next potential future state in an evolutionary process. My focus in the class is to help students understand that we don’t always know ahead of time what the adjacent possible could be in life but with preparation and focus we can be ready for it when it emerges. In this way we have the agency to create change responsibly.

I like to end this class by having the students (who are also in their final semester of a graduate program) to consider where they want to be in five years. In part what I hope they will understand is that the daunting next steps they face as they re-enter the world of work are more than just the immediate challenges of getting a job. They also set in motion a series of choices that will lead them into their own futures.

Of course there is the usual interpretation of work - What do you want to do? But there is another important question that I ask them - How do you want to do?

The point behind this admittedly awkwardly worded question is to get the students thinking about how the work that we do impacts the way we go through life. We are all concerned with work that will give us the means to live and hopefully will also reflect a meaningful contribution to things that we believe in. What we also need to think about is how that work will make us feel every day. Do we work with people that inspire us? Do we work in an office? Do we get to spend time outside? Do we have to spend all day on Zoom? Do we have to wear a tie? There is no question too trivial, because when all is said and done these are the things that define the texture and quality of our lives. Beautifully, there is not right answer to these questions but there is a right answer for each of us.

Of course we can’t always get what we want all of the time but if we think about these questions and really try, my hope is that when we tell the story of the work we have done and are doing, we will do it with the same amount of joy that is so obvious in the voice of Todd J. Barber.

The sheer effort that in providing tech support to a spacecraft 15 billion miles away cannot be minimized. Some people might also wonder - what is point of it all? For my part, I think it is important work and also frankly really cool. But the point I am trying to make is that for Todd and his fellow engineers, this work is deeply meaningful, for the scientific accomplishments sure, but also for the collaborative effort that it took to solve this problem. Todd’s work is precisely how he wants to be working. This alignment with his how is what I think causes the obvious joy and pride in his telling of the story. He is doing just what he wants to be doing and the years spent on this project are something that he will always be glad he spent his time doing. I suspect that when the work is finally done, his only regret will be that there is not more of it to do.

As humans we have the ability to collaborate and to create whatever world we want to create. Sadly this is not always the first thing on our minds when we set out to do the work of each day. It can be hard to see the adjacent possible that we are striving for. So I try to step back once an awhile and ask myself it the things that I am doing really reflect my own how and if I am playing a tiny part in creating the world that I want to be living in. Maybe if we get that right some of that world we make, will also be discovered in another world billions and billions of miles distant from the one we know. It turns out the adjacent possible is pretty big indeed.

I really loved this piece. So thought-provoking, as all of your work is.